Trends in Neural Machine Translation

2016-08-08

The following blog post was written as an attempt to summarize some of the important things happening in the field of neural machine translation (NMT). It was also a way of digesting a great tutorial on NMT given Sunday, August 7 at ACL in Berlin by some of the best people in the field: Christopher Manning, Minh-Thang Luong, and Kyunghyun Cho.

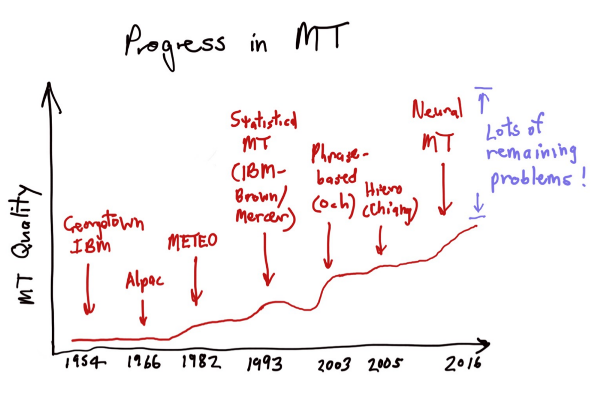

Machine translation has gone through a number of stages in the last decades. Phrase based statistical machine translation (SMT), the flavour used in systems such as Google Translate have seen little improvement over the last three years. Instead, people have been turning their heads towards neural machine translation (NMT) systems, which after being introduced seriously in 2014 have seen many refinements. These systems are also known as sequence-to-sequence models or encoder-decoder networks, and were initially fairly simple neural network models made out of two recurrent parts. Firstly, an encoder part taking an input sentence in the source language and computing an internal representation, and secondly the decoder part, a neural language model trained to be good at assigning a high probability to a well-formed sentence in the target language, which can be used to generate sentences that sound very good. Letting the language model be conditioned on the input turns it into a translation model. (See Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks Ilya Sutskever, Oriol Vinyals, Quoc V. Le. NIPS 2014, PDF, arXiv). These early NMT systems worked on word level, which means that a word is seen as a symbol, so the input to the encoder is a unique index for each unique word, and the decoder being constrained to pick words from this vocabulary.

These models worked well and got some promising scores in evaluations, but they had some drawbacks. Firstly, the longer the input sentence, the more difficult for the encoder to capture all important information in the internal fixed-size representation. Secondly, they are practical only for use with a fairly limited vocabulary size.

The former of the two problems were addressed in 2015, with the introduction of the attention models, allowing for the decoder part to “attend” to different parts of the input while generating the output. This is also used in multi-modal models for tasks such as image captioning where the attention mechanism allows the decoder to focus on different parts of the input image as it generates the output text.

The latter of the two problems has previously been addressed by letting the NMT system output special <UNK> tokens for words that are out-of-vocabulary (OOV) and post-processing the output by replacing this with the correspondng word in the source sentence, or looking them up in a dictionary (See “Addressing the Rare Word Problem in Neural Machine Translation” by Minh-Thang Luong, Ilya Sutskever, Quoc Le, Oriol Vinyals, Wojciech Zaremba. ACL 2015 PDF, arXiv ). This can result in the translated word being in the wrong inflection, or (worse) the word might not be in the dictionary at all (e.g. misspelled words). Better handling of OOV terms has been the focus of some work during 2016, and the topic of a couple of papers being presented during ACL 2016, taking place this week in Berlin.

In Neural Machine Translation of Rare Words with Subword Units by Rico Sennrich and Barry Haddow and Alexandra Birch from University of Edinburg (PDF, aclweb.org), a system is proposed that work on subword units. Words are segmented using the Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) algorithm (read about this on Wikipedia) into subword units of different length, and a vocabulary is built using frequent such units. The method internally creates embeddings for these subword units, something that has been criticized for making it lack the ability of relating words to each other. Rico Sennrich however argued during his talk that there is no reason why the word boundaries would be the best unit to have embedded. There are examples of composite words in one language that translates into a sequence of words in another language. The model is rather simple and elegant, and gets good BLEU scores (read more on BLEU on Wikipedia) translating between German and English, as well as Russian and English.

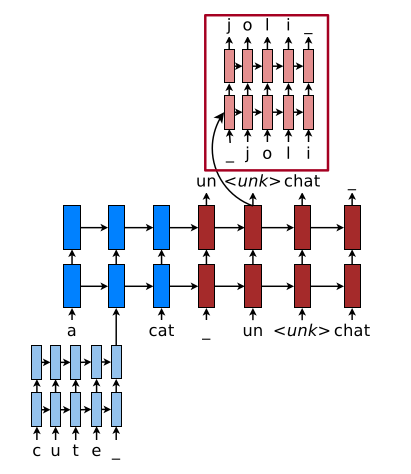

A second paper, by Junyoung Chung, Kyunghyun Cho, and Yoshua Bengio from New York University and Université de Montréal, titled A Character-level Decoder without Explicit Segmentation for Neural Machine Translation (PDF, aclweb.org), presents a model that also uses a vocabulary generated with BPE (see above) in combination with a “bi-scale recurrent neural network”, a recurrent network with GRU cells on two different time-scales, giving it a sense of hierarchy. The authors conclude that using the BPE tokens in the encoding part, along with a pure character-based decoding part, produces the best translations. The evaluation is made on four different language pairs: English-German, English-Russian, English-Czech, and English-Finnish.

In Achieving Open Vocabulary Neural Machine Translation with Hybrid Word-Character Models by Minh-Thang Luong and Christopher D. Manning from Stanford (PDF, aclweb.org), a model is presented that works as a normal word-based sequence-to-sequence model, as long as you feed it words in the vocabulary. When the model encounters an OOV term, the system employs a second sequence model working on character level. This model computes a representation for any word that is expressible in the given set of characters, and experimental results show that the representations computed in this way share many of the properties of neural word embeddings computed on word-level (read more on Word embeddings on Wikipedia). The system shows large improvements in BLEU scores, especially when used with a small word vocabulary, on the task of translating between Czech and English.

These are some of the more interesting presentations that I look forward to during this year’s ACL.

Olof Mogren